- You are here:

- Home

- >>

- William Shakespeare

- >>

- WS School

|

A BRIEF HISTORY OF

THE GRAMMAR SCHOOL

STRATFORD-UPON-AVON

Robert de Stratford, |

Thomas Jolyffe, |

This guild, unlike a trade guild, was a religious fraternity based in Stratford which supported a priest to offer prayers daily for the eternal salvation of its members' souls. The Guild of the Holy Cross, which was founded about 1269 by Robert de Stratford, also concerned itself with the material welfare of its members. It provided a hospital and almshouses in the town, held regular feasts and must also, at an early stage, have turned its attention to educating the young. The first recorded schoolmaster in the town was ordained "Richard, rector scholarum" in 1295 and, although this priest may have been associated with the parish church, it is more likely that he was supported by the Guild to teach its members' sons Latin grammar. Latin was required not only for entrance to university and the three professions -namely law, medicine and the Church but also by those in business or local administration for the keeping of records.

At the beginning of the fifteenth century the Guild embarked on a substantial building programme which included the Guildhall, today used by the School, but which was originally built as a feast-hall. |

| Figures from the stained-glass in the Guild Chapel | ||

The schoolroom was originally in the purpose-built Schoolhouse which was added in 1427. Now known as the Pedagogue's House, this is the oldest surviving half-timbered school building in the country and is still used by the School. The account for building it also survives and shows that it cost a little under ten pounds to construct, the timber costing forty-five shillings (£2.25). The schoolroom was originally in the purpose-built Schoolhouse which was added in 1427. Now known as the Pedagogue's House, this is the oldest surviving half-timbered school building in the country and is still used by the School. The account for building it also survives and shows that it cost a little under ten pounds to construct, the timber costing forty-five shillings (£2.25). Even more significant than the building of the Schoolhouse was the endowment made to the School in 1482 by one of the Guild's priests and a former pupil of the School, Thomas Jolyffe. The income from the land and property in and around Stratford which he gave more than anything helped to secure the future of the School. A salary of ten pounds was to be paid annually to a priest fit to teach grammar freely to all scholars coming to him to "school". Even more significant than the building of the Schoolhouse was the endowment made to the School in 1482 by one of the Guild's priests and a former pupil of the School, Thomas Jolyffe. The income from the land and property in and around Stratford which he gave more than anything helped to secure the future of the School. A salary of ten pounds was to be paid annually to a priest fit to teach grammar freely to all scholars coming to him to "school".

Some of the masters who first benefited from this endowment are known to have gone on to greater things, indicating that the Guild was employing men of great intellect and ability. Richard Fox, who was appointed master in 1497, later became principal minister under Henry VII, Bishop of Winchester and founded Corpus Christi College, Oxford. Brasenose College was also founded by a former master of the School, William Smyth.

The stature of the School by the beginning of the sixteenth century reflected the ever increasing importance of the Guild in Stratford which, in common with other guilds elsewhere, had amassed considerable property and wealth over the centuries. However, for reasons similar to those which resulted in the dissolution of the monasteries, the Crown set about dissolving the guilds in fear of the great power these institutions wielded.

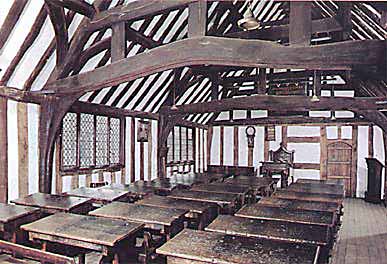

The Guild of the Holy Cross survived until 1547, when it too was dissolved. Six years later, in 1553, its buildings, its assets and many of its civic functions, including the responsibility of maintaining the School, were transferred by King Edward VI's commissioners to a newly formed Borough Corporation. Thus, the School was re-endowed: "we by the tenor of these presents, create, erect, found, ordain and establish to endure for ever a Free School in the said Town and the said school so by us founded shall be called and named in the vulgar tongue 'The King's New School of Stratford-upon-Avon'.  The new Corporation had no use for the upper floor of the Guildhall, so the School was transferred to this large room, now known as Big School, and the old Schoolhouse across the courtyard became the schoolmaster's residence. The Corporation continued to occupy the lower floor of the Guildhall and the adjoining Council Chamber and it was not until the end of the nineteenth century that the School was also given the use of these rooms. The new Corporation had no use for the upper floor of the Guildhall, so the School was transferred to this large room, now known as Big School, and the old Schoolhouse across the courtyard became the schoolmaster's residence. The Corporation continued to occupy the lower floor of the Guildhall and the adjoining Council Chamber and it was not until the end of the nineteenth century that the School was also given the use of these rooms.One of the first boys to have been educated at the King's School was William Shakespeare who would have entered at about the age of seven. The school day must have been very tiring for these young boys, starting at six o'clock in the morning during summer and continuing until five o'clock, with a two hour break at midday. In winter, although boys were expected to bring their own candles, the poor light meant a shorter day from seven o'clock until four o'clock.  The School continued to concentrate on teaching Latin. The boys learnt the rudiments with the assistance of the Tudor text-book known as Lily's Latin Grammar before studying the works of the great classical authors. By the time William was eleven the master was Thomas Jenkins, whose Welsh origins are shared by the comical schoolmaster, Sir Hugh Evans, in "The Merry Wives of Windsor". William also referred to the "whining schoolboy, with his satchel and shining morning face, creeping like snail unwillingly to school". Although he may have been a keen and intelligent scholar, later drawing on many of the classical tales he had studied, it may be that he did not altogether enjoy his schooldays. Certainly the regime was very strict, with boys punished if they spoke in English to one another instead of Latin. The School continued to concentrate on teaching Latin. The boys learnt the rudiments with the assistance of the Tudor text-book known as Lily's Latin Grammar before studying the works of the great classical authors. By the time William was eleven the master was Thomas Jenkins, whose Welsh origins are shared by the comical schoolmaster, Sir Hugh Evans, in "The Merry Wives of Windsor". William also referred to the "whining schoolboy, with his satchel and shining morning face, creeping like snail unwillingly to school". Although he may have been a keen and intelligent scholar, later drawing on many of the classical tales he had studied, it may be that he did not altogether enjoy his schooldays. Certainly the regime was very strict, with boys punished if they spoke in English to one another instead of Latin.Boys usually left the School about the age of fourteen, some to study at Oxford or Cambridge. However, William was probably withdrawn a year earlier by his father who by then was in financial trouble, explaining why the poet never had a university education. |

|

This pattern of education continued over the next two centuries. The standing of the School, however, slowly declined, despite the appointment of a number of distinguished schoolmasters. John Trapp, who came to the School in 1629, was a scholar of renown and the author of numerous commentaries on the books of the Bible. During the Civil War he sided with the Parliamentarians, becoming chaplain of the Stratford garrison, but following the recapture of the town by the Royalists, this schoolmaster was carried off to Oxford and imprisoned there for a time.

There next came a rapid succession of masters, all of whom suffered from ill-health and, indeed, several died soon after being appointed. The quality of the School thus suffered through unfortunate neglect. The number of pupils dwindled so that when the Revd Joseph Greene, a distinguished parson and antiquary, was appointed master in 1735, there was only a very small number of boys. As Greene observed; "the small-pox is ruining my school as fast as it can". By the time he left, thirty-seven years later, the number had increased to almost twenty but, within two years, there was again only a handful at the School. To supplement the master's salary Greene and his wife boarded the son of a local squire, James West. Greene wrote numerous letters concerning the child's progress in mastering Latin grammar, but seems to have been principally concerned with the health of this delicate pupil. There is mention of coughs and toothache and assurances that the parents' instructions on diet are being followed: "allowing him meat but sparingly, if it be such as is reckoned not very easy of digestion, but substituting pastry". In 1811, in response to a changing society in which an education based almost entirely on Latin was becoming inadequate, free tuition at the School was extended to include English grammar, reading and spelling. Subjects such as handwriting and arithmetic still had to be paid for at a rate of three guineas (£3.15) per subject, per year and the boys were also expected to pay 2s 6d (12½p) annually for coal. The School's limited resources were nevertheless fully stretched and it was unable to compete with the more relevant curricula offered by the private schools which were being established in the town. By the time the Revd Robert Stuart de Courcy Laffan was appointed headmaster in 1885, the administration of the School had been passed to a separate governing body and fees had been extended to cover tuition in all subjects. With these changes Laffan was able to transform the reputation of the School. A man of great insight and ability, he widened the curriculum to include more science and languages and thereby helped to attract more pupils, increasing the roll from under forty to over a hundred. The boarding side of the School was developed, the number of masters was increased to ten and additional classrooms and laboratories were built. The medieval buildings, which during the previous century had been covered with a disfiguring layer of roughcast, were fully transferred to the ownership of the School. Laffan instituted a programme of restoration to strip off this roughcast and to remove the low ceilings which, in Big School, revealed the original roof-trusses. All this work was paid for by Charles Flower, a former pupil at the School, who was also responsible for the building of the original Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford. Laffan was also responsible for starting the annual ceremony of laying flowers at Shakespeare's grave on the poet's birthday. This began as a simple school custom but, over the years, has developed into an international occasion, although the headmaster, staff and boys still lead the procession of civic leaders and foreign dignitaries to the parish church. After Laffan's departure, the School continued to flourish and, with the system of fees continuing, it assumed a status similar to a minor public school. However, the 1944 Education Act required the School to decide whether it wished to become a fully independent school or to be part of the State system of education. It chose to become a voluntary aided school as part of the State system. Leslie Watkins was appointed headmaster in 1945, the first in the history of the School not to be ordained, and both he and subsequent headmasters were to see the School rapidly develop under the influence of its changed status. |

John Trapp |

Joseph Greene | |

Robert Laffan |

|

Leslie Watkins |

|

All fees were to be abolished: boarders were no longer to be accepted; and the preparatory school. which had existed at various times since the 1880's, was to close. Boys, after taking a selection examination, were to enter at the age of eleven and to stay for up to seven years. The five core subjects of english, mathematics, french, religious instruction and physical education were supplemented by a wide range of options.

The School has since grown to accommodate over 400 boys and has facilities which include a drama stage, swimming pool and technology block.

It would be difficult to predict accurately what lies in the future for the School, but from the evidence of the past it seems certain that it will continue to face, adapt to, and satisfy contemporary needs. QuinSolve gratefully acknowledges the kind permission of the Guild School Association and Jarrold & Sons Ltd. Norwich to reproduce the above information on Shakespeare's School |